We begin the history of Christmas far earlier than the Christian era, rooted in powerful seasonal rituals tied to light, darkness, and rebirth. In the heart of the ancient Roman Empire, winter marked a dramatic turning point in the solar year. The festival of Saturnalia celebrated chaos, social reversal, feasting, and gift-giving. Homes were filled with evergreen decorations, candles symbolized returning light, and communities embraced joyful excess during the darkest days.

North of Rome, Germanic and Nordic peoples observed Yule, a multi-day observance tied to the winter solstice. Bonfires, decorated trees, and the honoring of ancestral spirits formed the spiritual backbone of winter celebration. These pagan traditions introduced enduring symbols that later fused seamlessly into Christian observance, including the Yule log, evergreen wreaths, and the powerful motif of light conquering darkness.

The Birth of a Christian Festival

The turning point in the formalization of Christmas emerges with the rise of Christianity in the fourth century. While the Bible provides no specific date for the birth of Jesus Christ, Church leaders strategically aligned the celebration with existing winter festivals. This transition allowed Christian theology to replace pagan symbolism while preserving popular traditions of feasting, light, and generosity.

Under the direction of Pope Julius I, December 25 was officially designated as the feast of the Nativity. This decision unfolded during an era shaped by Constantine the Great, whose reign legalized and strengthened Christianity as the dominant spiritual force of the empire. The theological framework supporting the birth of Christ was further refined at the Council of Nicaea, anchoring Christmas within orthodox Christian belief.

Medieval Christmas and the Rise of Communal Celebration

During the Middle Ages, Christmas became an immersive social and religious experience. The season expanded into a twelve-day festival filled with nativity plays, communal banquets, and public rituals blending sacred and secular life. Lords opened their halls to peasants, food flowed freely, and communities gathered for shared celebration rarely matched during the rest of the year.

The medieval Church formalized liturgical traditions such as Midnight Mass, candlelit processions, and choral worship. At the same time, folklore figures emerged to personify generosity and moral instruction. Among the most influential was Saint Nicholas, a third-century bishop from Myra known for secret gift-giving and protection of children. His legend gradually spread across Europe and planted the spiritual foundation for the modern gift-bringer.

Reformation Tensions and the Reinvention of Tradition

The sixteenth century brought monumental upheaval with the Protestant Reformation. In many regions, Christmas faced outright suppression. Puritan authorities in England and parts of colonial North America condemned the holiday as a remnant of pagan excess. For decades, public celebrations were restricted, carols were silenced, and festive customs were discouraged.

Yet cultural memory proved resilient. Christmas survived in households through private observance, culinary traditions, and storytelling. These quiet forms of resistance preserved the emotional heart of the holiday until revival became possible.

Victorian England and the Modern Christmas Revival

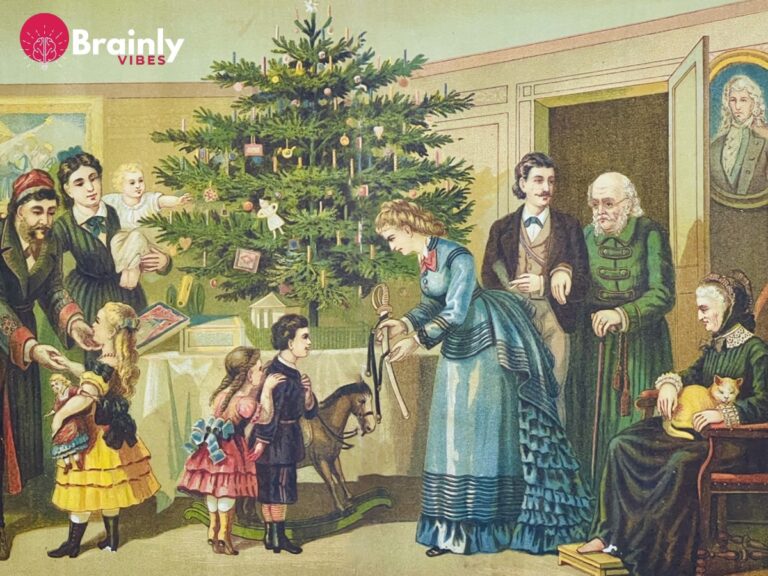

The true rebirth of Christmas as we know it today occurred in Victorian England. Industrialization had transformed society, often eroding family cohesion and communal warmth. Christmas re-emerged as a moral counterbalance, emphasizing domestic unity, charity, and child-centered joy.

The literary force behind this transformation was Charles Dickens. His seminal work, A Christmas Carol, reshaped public imagination. The story elevated themes of redemption, social responsibility, and compassion for the poor, anchoring Christmas as an ethical as well as festive season. Tree decorating, card sending, and structured gift exchange became standardized practices during this period.

The Transformation of Santa Claus into a Global Icon

Across the Atlantic, Saint Nicholas evolved into a uniquely American figure. Dutch settlers carried the legend of Sinterklaas to New York, where folklore blended with commercial innovation. The rotund, red-suited Santa familiar today took form in the twentieth century through mass media and advertising.

A defining moment came through artwork commissioned by Coca-Cola and illustrated by Haddon Sundblom. This imagery standardized Santa as a warm, benevolent patriarch dressed in vibrant red, reinforcing Christmas as a season of joy, abundance, and family-centered magic across the globe.

Christmas in Times of War and Global Crisis

Even amid conflict, the power of Christmas has repeatedly asserted itself. During World War I, one of the most moving episodes in holiday history unfolded with the 1914 Christmas Truce. Soldiers on opposing sides emerged from trenches to exchange gifts, sing carols, and share food. For a single night, humanity transcended warfare through the shared language of Christmas.

In the twentieth century, radio, cinema, and later television carried Christmas into every household. The holiday became both a cultural unifier and a commercial powerhouse, balancing sacred observance with secular celebration.

Urban Spectacle and the Rise of Public Tradition

As cities expanded, Christmas shifted into the public sphere on an unprecedented scale. The lighting of the tree at Rockefeller Center emerged as one of the most visible modern rituals of the season, symbolizing resilience, prosperity, and collective celebration during the Great Depression and beyond.

Parades, department store window displays, and public charity drives transformed Christmas into a civic event. The season became inseparable from organized generosity, linking gift-giving to humanitarian ideals promoted by institutions such as the United Nations, which later framed December as a period for global solidarity and human rights reflection.

The Globalization of Christmas Across Cultures

By the late twentieth century, Christmas had transcended its Western Christian origins to become a global cultural phenomenon. In East Asia, it developed into a romantic and commercial holiday. In parts of Africa, it blended with indigenous rhythms and community feasts.

Despite regional variation, several universal constants define modern Christmas:

- Light as a symbol of hope

- Gift exchange as an expression of love

- Communal meals as bonds of unity

- Music as emotional storytelling

- Charity as moral purpose

These elements knit together millions of interpretations into a single shared global tradition.

The Enduring Meaning of Christmas in the Modern World

Today, Christmas stands at the intersection of faith, culture, commerce, and memory. For believers, it remains the celebration of divine incarnation. For secular families, it represents closeness, generosity, and emotional renewal. In societies, it serves as an annual pause for reflection, reconciliation, and shared humanity.

What makes the history of Christmas uniquely powerful is its capacity to absorb change without losing identity. It has absorbed pagan ritual, imperial strategy, medieval devotion, reformation controversy, literary renewal, commercial imagery, and global digital culture—yet its emotional core remains unmistakably intact.

We observe in Christmas not a static holiday fixed in time, but a living tradition, reshaped by every generation while preserving its oldest truths: that light returns, kindness matters, and community overcomes isolation.

Conclusion: A Tradition That Continues to Evolve

The history of Christmas is not merely a timeline—it is a record of human longing for meaning during the darkest season of the year. From solstice rituals and imperial decrees to novels, advertising, and global diplomacy, Christmas reflects the story of civilization itself.